Training Frontline Workers in Satna Strengthens Family Planning Supply Tracking and Ensures Uninterrupted Access to Commodities

Contributors: Radha Pradhan, Trupti Sharma, Prabhat Kumar Jha, Deepti Mathur, and Parul Saxena

The hands-on training has empowered our ANMs and ASHAs to manage family planning commodities independently and accurately. This has greatly improved stock availability across the city.”

Manisha Kushwaha

Nursing Officer, District Hospital, Satna, Madhya Pradesh

In Satna, Madhya Pradesh, city health officials identified major gaps in the use of the Family Planning Logistics Management Information System (FPLMIS)—a key tool for tracking and ordering commodities. For nearly five years (2018–2023), urban health facilities had neither placed nor recorded any family planning commodity orders through the system. Most frontline workers lacked FPLMIS IDs or the skills to operate the platform. This created repeated delays, poorly managed stock, and inconsistent availability of essential commodities across health centers.

The Nodal Officer highlighted FPLMIS issues to the Chief Medical & Health Officer (CMHO), who directed immediate action. FPLMIS IDs were quickly generated for all ASHAs and ANMs across and rapid hands-on training sessions were organized. PSI India and the district health team jointly trained approximately 104 ASHAs and 45 ANMs on creating IDs, generating passwords, requesting family planning commodities, and maintaining inventory records.

The hands-on demonstrations and peer learning models helped workers understand the system with ease. Manisha Kushwaha, said: “Since September 2024, all ASHAs and ANMs across five Urban Community Health Centers and two UPHCs are successfully identifying family planning commodities themselves. This has led to improved data management, uninterrupted stock supply, and timely commodity distribution."

District authorities further reinforced the process by integrating FPLMIS tracking into monthly review meetings. Supervisors regularly monitored indenting practices and ensured timely resolution of stock-related issues. As a result, Satna’s family planning supply chain has transitioned from irregular and unmonitored processes to a structured, reliable, and sustainable system. Community members now experience consistent access to family planning methods and services—a significant step toward improved reproductive health outcomes in the city.

Four Girls Who Chose Hope Again

Contributors: Priyank Trigunayat, Amit Kumar, Deepti Mathur, Parul Saxena

PSI India is doing remarkable work by ensuring that girls who had almost lost their connection with education are brought back into the school. Their consistent follow-up, counselling, and coordination with educational institutions and families truly make a difference. If we can support them in any way, we are always ready. Together, we can help these children build a brighter future.”

A teacher, Composite School

Gauri Bazaar, Deoria, Uttar Pradesh

During a door-to-door visit in Ubhav village of Deoria district, Uttar Pradesh, the Maitri–Vidya team met four girls whose lives reflected both hardship and resilience. Three of them—Aanchal, Payal, and Bittu were sisters, while their friend Shalu was neighbour. All four had lost their fathers at a young age and were being raised by their mothers alone. Aanchal and Shalu, who were of the same age, had dropped out of school during the COVID-19 pandemic when they were in Class 3 and had not returned since.

Aanchal and her sisters’ situation was especially challenging. After their father passed away, their mother Maina Devi faced mistreatment from her in-laws and had to move back to her maternal home in Ubhav with her daughters. To earn a living, she travelled to Gorakhpur for labour work, leaving Aanchal, the eldest, responsible for managing the household and caring for her younger sisters.

The team escalated the situation to the district office and sought support to obtain the documents require for school admissions. On their next visit, they counselled the mother and encouraged her to enroll the children in a school located in the neighbouring village, explaining how education could change their lives and improve the family’s long-term financial stability. With time and reassurance, the mother agreed. However, Shalu still refused. Determined not to leave her behind, the team visited her home along with Aanchal and spoke gently to her mother. After thoughtful conversations and persistent persuasion, Shalu finally changed her mind and expressed excitement about attending school with her friends.

The Maitri–Vidya team then approached the Composite School in Gauri Bazaar and advocated for the enrolment of all four girls. The teachers appreciated the effort and assured full cooperation, including support for completing the necessary documentation to ensure a smooth admission process. Soon after, the team took all four girls to the school, where they met the teachers, explored the classrooms, and saw the available facilities. Their mothers were also informed about the arrangements for the students. Based on age-appropriate placement, Aanchal and Shalu were enrolled in Class 6, while Payal and Bittu were placed in Class 2. The very next day, the girls returned to school, received their textbooks, and began attending regularly with a renewed sense of hope.

PSI India’s efforts under the Maitri–Vidya project are rooted in the belief that educating girls is one of the most powerful pathways to social and economic transformation. By identifying around 3,500 Out-of-School Girls across two blocks of Deoria district, PSI India is helping bring them back into classrooms. The enrolment of these four girls represents not just a single success story but is part of a larger commitment to ensuring that more Out-of-School Girls reclaim their right to learn, grow, and build a better future for themselves.

Rebuilding Hope Through Consistent TB Treatment

Contributors: Naveen Kumar Bansal, Deepti Mathur, Parul Saxena

PSI India team gave me a second chance when I had lost all hope. Their visits, their support, and their belief in me brought my life back on track. I will always be grateful for the care they showed to me and my family.”

Jitendra Kumar

Gautam Buddh Nagar, Uttar Pradesh

India continues to shoulder one of the world’s highest tuberculosis (TB) burdens. Yet, recent years have witnessed a remarkable decline in TB-related deaths, driven by stronger national and state action under the National TB Elimination Programme (NTEP). Uttar Pradesh remains central to this fight, accounting for nearly one in five TB cases in the country.

Amid these efforts emerges the deeply moving story of Jitendra Kumar, a 35-year-old father of three from Karmaspur village in Dankaur block, Gautam Buddh Nagar, whose struggle with TB reflects both the fragility of poverty and the power of collective support.

Jitendra, a daily-wage laborer and the sole provider for his family, often struggled to ensure even two meals a day. Persistent fever and coughing went untreated, weighed down by financial hardships and emotional exhaustion. Only after repeated insistence from his wife did he visit Primary Health Center (PHC) Dankaur, where doctors suspected TB. His sputum test confirmed the diagnosis on 8 December 2024, and treatment began shortly after. He diligently completed 56 doses.

But fate took a difficult turn. A land dispute case led to his arrest, keeping him in jail for three months. His treatment stopped abruptly. The setback crushed his will. Even after returning home, he couldn’t bring himself to restart medication. His health deteriorated rapidly, leaving the family terrified and helpless.

The breakthrough came unexpectedly, through a child’s courage.

During PSI India’s awareness drive in the locality, a soft, trembling voice cut through the air: “My father is not well. He keeps coughing all night, has fever, and he doesn’t eat much. Our father is the only one who earns for us. Please come again and check him. It will help us a lot.” It was Jitendra’s 12-year-old son.

The very next day, PSI India’s TB-STRIVE field team visited their home. After screening and sputum collection, results confirmed TB once again on 22 August 2025. Treatment was restarted on 28 August under the same NIKSHAY ID. Weighing only 39 kg, Jitendra was immediately linked to the Nikshay Poshan Yojana to ensure nutritional support. Efforts were also initiated to connect him with a Nikshay Mitra, a community volunteer who could stand by him and his family throughout the treatment journey.

Under the TB-STRIVE Project, PSI India has strengthened TB detection and care across intervention districts by screening 9,554 individuals, identifying 2,178 presumptive TB cases, and ensuring that 172 diagnosed patients were promptly linked to appropriate treatment services. Working closely with the Government of Uttar Pradesh, PSI India is mobilizing communities through focused awareness drives, supporting early detection and timely notification, and enabling consistent treatment adherence through regular follow-ups and counselling. Collectively, these efforts are helping build a more responsive, community-driven TB care ecosystem and accelerating India’s progress toward eliminating tuberculosis.

A New Chapter in the Life of Sahabganj UPHC

Contributors: Naushad Ali Shah, Amit Kumar, Deepti Mathur, Parul Saxena

With PSI India’s support, our services became structured, data-driven, and far more effective. Today, women trust us, and we are confident in delivering PPIUCD services.”

Staff Nurse

Sahabganj Urban Primary Health Centre (UPHC), Farrukhabad

The Sahabganj UPHC, Farrukhabad, Uttar Pradesh, inaugurated in 2014, serves a population of nearly 50,000. It is staffed by a dedicated team consisting of one MOIC, two staff nurses, three Auxiliary Nurse Midwife (ANMs), one laboratory technician, one pharmacist, one ward nurse, and 11 Accredited Social Health Activists (ASHAs) workers responsible for community mobilization. Although delivery services began in January 2015, postpartum IUCD (PPIUCD) services could not be offered for several years due to the absence of trained staff. This gap was finally addressed in November 2020, when the district organized PPIUCD training for both staff nurses. Even after training myths, low community awareness, and staff hesitation hindered PPIUCD uptake.

The staff nurses and ANMs were coached on effective counseling skills, while ASHAs were strengthened to expand their outreach, dispel myths, and promote institutional deliveries and PPIUCD services. Engaging Mahila Arogya Samiti members further strengthened community participation and helped connect women to essential maternal and child healthcare services. National Health Mission officials actively participated in UPHC-level meetings, motivating the staff and boosting their confidence.

Regular ASHA–ANM meetings created a platform for sharing knowledge, reviewing progress, and addressing gaps. Meanwhile, PSI India introduced the UPHC staff to TCI University, enabling them to adopt evidence-based high-impact interventions and practices for family planning. With PSI India’s continued support, services gradually became more structured, data-driven, and effective in improving maternal health, child care, and family planning outcomes.

As a result of these collective efforts, the UPHC achieved what once seemed impossible. From having no PPIUCD insertions in 2021–22, the UPHC recorded an 80% insertion rate against total deliveries in 2022–23, which further increased to 95.7% in 2023–24. These achievements were celebrated in monthly review meetings, reinforcing the dedication and commitment of the UPHC team.

The Power of Partnership: Making It Happen

Contributors: Khushbu Kumari, Nilesh Kumar, Deepti Mathur, Parul Saxena

To deliver what you promise—this is something I learned from PSI India. Their support gave wings to our efforts and renewed confidence to our health facility staff.”

Manish Kumar

City Urban Health Manager (CUHM), East Singhbhum, Jharkhand

In East Singhbhum, Jharkhand, the National Urban Health Mission (NUHM) unit and City Urban Health Manager (CUHM) Manish Kumar have been instrumental in strengthening family planning services through their partnership with PSI India inder The Challenge Initiative (TCI) India.

The NUHM unit in East Singhbhum embodies the guidelines, protocols and the vision set by Government of India. However, to effectively implement both budgeted and non-budgeted activities, cities requires additional support. To bridge the gap, PSI India team identified key gaps and initiated advocacy with the NUHM officials.

“There were budgeted activity such as NUHM review meeting, City Health Coordination Committee meetings and family planning meetings at various urban health centres. However, due to the unavailability of NUHM team, these activities were infrequent. PSI India, through regular follow-up worked to ensure these critical meetings became consistent, as some had delays of 4 to 6 months. They engaged with several stakeholders, including District Program Manager, to address this issue. Thanks to PSI India's persistent efforts, these meetings have been held regularly since 2023.” -shares Manish Kumar

With NUHM officials focusing on management-related solutions, PSI India team provided coaching and technical support to address challenges faced by health facility staff.

“While we were in the driving seat of implementing interventions, the backup support provided by PSI India helped us quickly overcome challenges through systematic steps and effective strategies. Soon, the impact of this collaboration was evident,health services including family planning and counseling improved across several health facilities. If I must say, ‘to deliver what you promise’ is something I have learned from PSI India. We were making things happen at the urban level, it showed in data and in the newfound confidence of health facility staff. PSI India gave wings to my efforts to meet the needs of the masses,” -says Manish Kumar.

To further strengthen family planning services in the city, Manish organized a TCI India program review for progress-sharing using NUHM funds. This initiative helped revitalize family planning efforts in East Singhbhum.

Overcoming Vaccine Hesitancy: TCI Helps Build Trust and Protect Children in Hardoi District, Uttar Pradesh

Contributors: Dharmendra Singh, Ipsha Singh, Amit Kumar, and Parul Saxena

The only reason for opposition to vaccination is lack of information. It’s ironic that myths spread faster than facts. People don’t know how vital vaccines are for protecting children’s health. Sadly, misconceptions like ‘vaccines cause fever, swelling, or even physical harm to children’ continue to take root.”

Dr. R.K. Singh

District Immunization Officer, National Health Mission, Hardoi, Uttar Pradesh

In Hardoi district of Uttar Pradesh, routine reviews under the National Health Mission revealed a critical gap: vaccination records maintained by health workers did not match the actual list of children due for immunization.

A subsequent gap analysis revealed a more troubling problem – 12 families in Khajanchi Tola, a locality in Hardoi, were actively resisting child vaccination. With PSI India’s support, Dr. Singh and his team devised a targeted plan to address the resistance in Khajanchi Tola.

Until then, each attempt to engage families had met with strong pushback. Dr. Singh highlighted the importance of clear communication: “People need to hear not only about the benefits of vaccination but also about the mild and temporary side effects, and this part is often overlooked.”

The team implemented a multi-pronged strategy. Auxiliary Nurse Midwives (ANMs) began connecting hesitant families with parents who had already vaccinated their children. These parents shared personal stories, reassuring others that their children remained healthy and that any side effects were brief and manageable. Even the local Sabhasad (councillor) joined the effort to promote immunization. To further build trust, a dedicated team – comprising the Medical Officer, Health Supervisor, and Pharmacist personally visited each of the 12 families. They used simple, relatable language to explain how vaccines work and how they protect children from serious diseases.

Gradually, the tide began to turn. Families’ trust in the healthcare system grew – not just in the vaccines but in the commitment of frontline workers. Free testing and ultrasound services for pregnant women at government facilities further reinforced confidence.

Dr. Singh’s face lit up with relief and pride as he shared the results: “Nine families eventually agreed to vaccinate their children. It was a real turning point. I’m sincerely thankful to TCI India for their consistent support, from monitoring and planning to hands-on coaching of our health teams.”

While the progress is notable, the work is not over. Dr. Singh remains determined: “We’ve come a long way, but challenges still remain. The mission isn’t over yet. Three families are still hesitant, mostly due to religious concerns, but we won’t rest until every single child in Khajanchi Tola is protected.”

Strategic Coaching and Advocacy Expand IUCD Access and Strengthen FP Services in Bhagalpur, Bihar

Contributors: Naveen Rai, Vivek Malviya, and Deepika Anshu Bara

With consistent coaching and availability of equipment, our Urban Primary Health Centers (UPHCs) finally became fully functional for IUCD services. Today, no woman is turned away due to lack of equipment or trained staff.”

District Program Manager

Bhagalpur, Bihar

Bhagalpur, a major city in Bihar, faced significant challenges in delivering quality family planning services. Before 2022, IUCD services were either unavailable or inconsistent across most UPHCs, leading to missed opportunities for clients seeking long-acting reversible contraception.

PSI India provided tailored coaching to local officials, emphasizing the importance of offering a broad method mix to support informed, voluntary family planning choices. Through this coaching, city teams began using routine forums – such Accredited Urban Health Activists (ASHAs) and Auxiliary Nurse Midwives (ANMs) meetings, data validation meetings, and National Urban Health Mission (NUHM) reviews to strengthen service delivery and coordination.

Yet, despite progress, a major bottleneck remained: each UPHC had just one IUCD kit for Fixed-Day Static (FDS) services. As demand grew, this shortage led to long wait times, missed opportunities, and discouraged clients. Performance monitoring data helped uncover a key factor – UPHCs with a higher number of ASHAs performed better, illustrating the critical role of community health workers in generating demand and supporting access.

PSI India also identified other system barriers, such as non-functional sterilization equipment that forced facilities to rely on nearby centers – delaying procedures and reducing service quality. In response, PSI India worked with Bhagalpur’s District Program Manager to escalate the issue to the Civil Surgeon. Despite funding constraints – urban health programs lacked their own budget lines – PSI India persisted through strategic advocacy and data-backed dialogue.

By January 2025, their efforts paid off. The Civil Surgeon approved the procurement and distribution of 32 IUCD kits and 8 forceps through the District Health Society, ensuring each UPHC received four kits to maintain uninterrupted service delivery.

The results speak for themselves. IUCD insertions in Bhagalpur rose from 0 in 2021 to 526 in 2025. The number of trained ASHAs increased from none to 46, significantly enhancing community outreach and counseling. Meanwhile, 24 service providers were trained in IUCD insertion, bolstering provider capacity and service availability.

Advocacy Leads to Initiation of Sterilization Services at Urban Community Health Centres

Contributors: Ruby Rout, Prabhat Kumar Jha, Deepti Mathur

PSI India presented an analysis showing the need for comprehensive services including sterilization at UCHCs. Their advocacy helped us strengthen awareness, availability, and accessibility of family planning services.”

Monalisa Nayak,

Nursing Officer, Municipal Corporation UCHC, Bhubaneswar, Odisha

Bhubaneswar, Odisha, is served by four Urban Community Health Centres (UCHCs) equipped to provide reproductive health services. While these centers had the infrastructure and client potential, they were not offering sterilization services. This created an added burden on Capital Hospital and limited access for urban families seeking permanent family planning options. Recognizing this gap, PSI India under The Challenge Initiative (TCI),India initiated advocacy with the Directorate of Family Planning, National Health Mission (NHM), and Bhubaneswar Municipal Corporation to expand the service package at UCHCs.

A series of discussions were held between the Directorate of Family Planning, National Health Mission officials, and the PSI India team. It was decided that challenges would be addressed in a phased manner: first, by increasing community awareness, and second, by equipping UCHCs to provide sterilization services.

As the first step, community sensitization programs were conducted through outreach camps, engaging local leaders and health officials to spread awareness about sterilization methods and available services. Accredited Social Health Activists (ASHAs) and Auxiliary Nurse Midwives (ANMs) were trained and supported in demand generation and client mobilization, ensuring informed decision-making among eligible couples.

“The outreach program was implemented under focused Fixed Day Static services on 16 January, 22 January, 6 February, and 22 February 2024. The outcome of these outreach camps was remarkable—mobilizing 35 female sterilization cases and one No-Scalpel Vasectomy (NSV),” shares Monalisa Nayak.

Infrastructure optimization was another key step. Although UCHCs had designated spaces for sterilization, they lacked essential equipment. To address this, Dr. Murali Dhar Padhi, Additional Director, Family Welfare and Maternal Health, provided personal laparoscopic equipment to support the UCHCs until they could be fully equipped.

“Refresher trainings were organized for the clinical staff of UCHCs. The capacity building of UCHC staff and medical officers enabled them to continue providing services without interruption. We consistently emphasized comprehensive pre- and post-operative counseling along with regular follow-ups. To assess progress and address concerns, regular meetings were held at both UCHC and district levels. This approach has helped Bhubaneswar move closer to its goal of comprehensive family planning,” adds Monalisa Nayak.

Bhubaneswar’s initiative exemplifies how collaborative efforts between the public health system and technical support partners can drive sustainable change, making comprehensive family planning services more accessible, especially for those who need them most.

Empowered Women, Healthier Communities: Strengthening MAS Groups to Enhance Community Accountability in Bihar

Contributors: Vivek Malviya, Jyoti Kumari, Deepika Anshu Bara, Manish Saxena, and Deepti Mathur

Visiting the health facility under the 'Know Your Facility' campaign gave me the opportunity to see firsthand the available services. Now, I confidently guide community on accessing health services. I have helped many couples to avail family planning services and maternal health services. It felt empowering to make a real difference.

A MAS member

Patna, Bihar

Community accountability is the cornerstone of public health. When individuals are empowered to monitor and influence health services, they become active stakeholders in their own well-being. The Mahila Arogya Samiti (MAS) women’s groups in India serves as a powerful vehicle for communities to take ownership of health initiatives, ensuring that health providers respond to local needs. Recognizing this, The Challenge Initiative (TCI) developed an innovative approach to revive MAS groups, in Bihar. In collaboration with urban primary health centers (UPHCs) and under the leadership of city health authorities, TCI launched the “Know Your Facility” campaign.

Through outreach camps and community engagement activities, the initiative introduced MAS members and their families to the range of services available at UPHCs. By offering firsthand experiences of government-provided healthcare, the campaign equipped MAS members with the knowledge and confidence to become health advocates within their communities. Special camps at UPHCs played a crucial role in this initiative, with Accredited Social Health Activists (ASHAs) mobilizing MAS members and encouraging facility visits. These visits familiarized women and their families with available health services, including family planning options.

By raising awareness about government-provided healthcare, MAS members were empowered to leverage their collective influence, promote community awareness, and drive positive change within families. Many expressed gratitude for the experience, as this was their first opportunity to engage directly with UPHC staff. Their confidence in accessing healthcare services grew, strengthening their role as community health ambassadors.

For instance, one MAS member recently assisted a pregnant woman in reaching the nearest health facility for delivery using untied MAS funds. This decisive action reflects the effective coaching provided by TCI, which has trained MAS members to prioritize urgent health issues such as maternal health and family planning. Members have also been trained in decision-making, identifying key health priorities – including heat wave preparedness, diarrhoea prevention, nutrition, healthy habits, and communicable disease control – and advocating for necessary services.

To ensure accountability and transparency, MAS groups receive printed registers to document meeting minutes and track fund utilization. Between April and November 2024, over 75% of MAS members underwent health check-ups at their assigned facilities, underscoring the growing awareness and engagement fostered by these initiatives.

A key success has been strengthening MAS governance. When an inactive secretary was identified, members democratically nominated a new leader, demonstrating their commitment to effective leadership and accountability. Beyond regular community meetings, the state government now conducts monthly online sessions with district health officials and development partners to discuss MAS strategies. These meetings provide ongoing training, reinforce community accountability, and address practical challenges such as funding for refreshments and materials. The MAS initiative in Bihar has emerged as a model for community-led health transformation.

Recognizing its impact, the government is now scaling it up across 22 additional non-TCI-supported cities. As part of this expansion, health cards have been developed for all MAS members in these cities. Once printed and distributed, these cards are expected to enhance healthcare access and improve overall well-being. This initiative stands as a powerful testament to the impact of women-led decision-making and community accountability in achieving sustainable health outcomes. By strengthening local leadership and fostering greater engagement, MAS continues to drive lasting change in Bihar’s public health landscape.

Celebrating Heroes: Bihar’s Heartwarming Initiative to Honor ASHAs and Boost Family Planning Efforts

Contributors: Manish Saxena, Vivek Malviya, Deepti Mathur, Parul Saxena, Hitesh Sahni and Mukesh Kumar Sharma

I never imagined something like this could be done for me. I had always observed the birthdays of others, but my birthday had never been celebrated like this before. For the first time, I cut a cake, and it felt incredibly special.

ASHA

Bhagalpur, Bihar

In October 2023, The Challenge Initiative (TCI) collaborated with the government in Bihar, India, to launch a unique and heartwarming initiative to honor and motivate the unsung heroes of India’s healthcare system: Accredited Social Health Activists (ASHAs).

ASHAs are frontline health workers that tirelessly bridge the gap between the community and the healthcare system, especially for family planning services. Recognizing their crucial role, the birthday initiative aimed to celebrate ASHAs during monthly meetings held at Urban Primary Health Centers (UPHCs).

Typically centered around coaching, planning, and reporting, these meetings took on new meaning with these heartfelt celebrations that profoundly touched the ASHAs. Many were visibly moved, with tears in their eyes as their birthdays were celebrated meaningfully for the first time. When asked about their experience, the ASHAs expressed they felt emotional, motivated, recognized, and respected.

During a master coach meeting, this initiative was discussed extensively, with plans to continue as a tribute to the ASHAs. Government officials supported the idea, recognizing the critical role ASHAs play in the community, far outpacing their position as volunteer workers. The officials present affirmed that this celebration was long overdue. One said: “ASHAs work tirelessly for everyone, and we felt it was time to recognize them.”

The Medical Officers in Charge at UPHCs also appreciated the birthday initiative, noting significant improvements in coordination and relationships with the community health workers. They observed that ASHAs felt more connected, leading to increased work efficiency. This newfound motivation resulted in better preparation of eligible family planning client lists, increased attendance at family planning fixed-day static services, and an overall rise in client flow at the UPHCs.

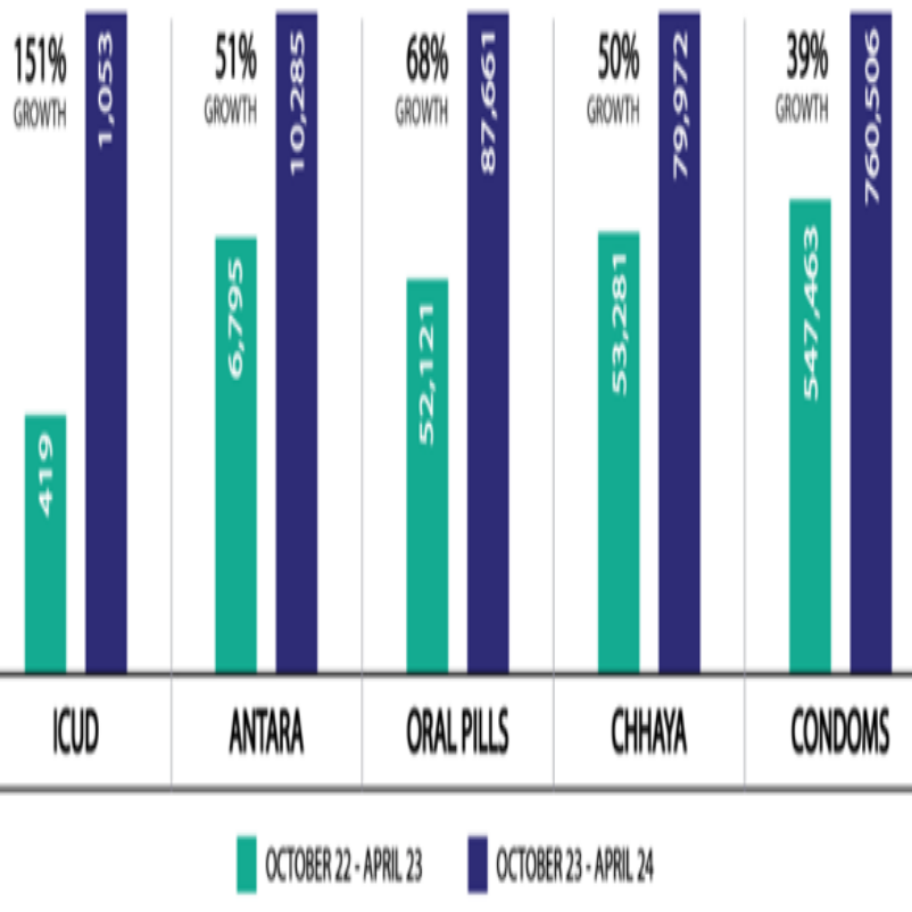

The graph illustrates a substantial increase in the uptake of modern contraceptives across 60 UPHCs in the seven TCI intervention cities in Bihar, correlating to increased ASHA activity. The significant rise highlights the impact of the ASHAs’ efforts in promoting and facilitating access to modern contraceptive methods within their communities.

Revamping Urban Sanitation: The Game-Changing Branding of Desludging Services

Contributors: Dinesh Kumar Pandey, Deepti Mathur and Parul Saxena

In partnership with PSI India, we transformed Lucknow's FSM landscape, tripling safe fecal sludge disposal from 25 lakh liters in January 2020 to 72 lakh liters by January 2021. Operators embraced tanker rebranding under Lucknow Nagar Nigam (LNN) guidelines, showcasing professionalism and their commitment to safe, reliable service.

Ram Kailash

Former General Manager, Jal Kal Department, Lucknow

In Lucknow, the capital of Uttar Pradesh, over 43% of households depend on septic tanks for sanitation, due to only partial connectivity to sewer lines, presenting a stark challenge. The unregulated and unsafe disposal of faecal sludge by private operators was a critical issue, leading to the contamination of water bodies and posing severe health risks. This sector was characterized by disorganization and a lack of regulation, actions that compromised its legitimacy and attracted scrutiny from local administration and police forces.

A key achievement of this collaboration was the registration of all 50 private desludging vehicles by the Jalkal Department of LNN, ensuring their safe disposal at designated Sewage Treatment Plants (STPs) and Sewage Pumping Stations (SPSs). Additionally, PSI India field team conducted community outreach to encourage the use of registered operators through the fecal sludge management (FSM) 14420 helpline. To ensure safe disposal, the vehicles were equipped with GPS trackers, monitored by the FSM call center in LNN. Moreover, the desludging workers were trained on standard operating procedures and mandatory use of personal protective equipment, for safe extraction, transportation and safe disposal.

However, despite these advancements, desludging operators continued to face social stigma and operational hurdles, highlighting the need for more substantial change. Moreover, the PTOs’ vehicles, often painted according to personal preference, contributed to a lack of professionalism and led to illegal recoveries by local police.

Underlining the importance of safety, professionalism and respect, a rebranding initiative led by PSI India and LNN was launched, resulting in the branding of all 50 private desludging vehicles and 4 vehicles owned by LNN. This effort involved securing approval for the use of government logos and adhering to an approved colour scheme. The logos included those of the Swachh Bharat Mission, Safai Mitra Suraksha Challenge (SMSC), LNN, Government of India, Swachh Survekshan, and the Malasur (Demon of Defeca) campaign, enhancing visibility and promoting safe, mechanized desludging while discouraging manual scavenging.

Moreover, the vehicles displayed a helpline number for the FSM call center and the LNN registration number, informing the public, police and government of the vehicles’ authorized status. Similar branding efforts were extended to public and community toilets across Lucknow, with ‘wall paintings’ done by involving community ward champions.

Ram Kailash, elucidated, "This comprehensive approach has not only fostered trust among the government and the community but has also instilled a sense of pride and legitimacy in the registered tankers. As a result, an additional 10 tankers have voluntarily embraced this branding at their own cost. The uniform branding and GPS tracking have improved service quality and accountability, reducing illegal dumping and police recoveries. The public now has ready access to a list of registered operators available on the LNN website, enhancing trust and service reliability."

The transformation from stigmatization to respect, from health hazard to health promotion, underscores the profound impact of strategic branding and collaborative efforts. It serves as an exemplary model for other cities facing similar challenges, demonstrating how to dignify essential services and safeguard public health through innovation, empathy and partnership.

Two Cities in TCI-Supported Jharkhand, India, Empower CHWs to Streamline Supply Chain Management

Contributors: Abhishek Kumar, Manjurur Rahman Khan, Deepika Anshu Bara, Sunil Kumar, Nilesh Kumar, Samarendra Behera and Deepti Mathur

After the coaching and mentoring received from the TCI India team, we realized that FPLMIS-indenting was meant to initiate from the CHW level so that they had timely access and could distribute to all needy beneficiaries.

Saifullha Ansari

City Community Process Manager, Bokaro, Jharkhand

An efficient and uninterrupted supply chain for family planning commodities is imperative for successful programming. The Family Planning Logistics Management Information System (FPLMIS) initiated by the Government of India revolutionized the health system by digitizing the supply chain. Yet it wasn’t yet active in some urban areas, as TCI witnessed in Bokaro and Deoghar, two cities in Jharkhand State.

Before TCI engaged with Jharkhand’s cities, a paper-based manual supply-chain system was in use that had many shortcomings, such as poor inventory management, a top-down push for commodities, no real-time, on-demand information on supplies, and difficulty in compiling and analyzing data at the district level. This led to overstocking at times, shortages at times, or complete stock-outs at times at different facilities. FPLMIS was a good solution but it had only been introduced in rural areas.

To streamline family planning commodities management using FPLMIS across health facilities, TCI advocated with the state’s family planning unit. The unit called for a joint meeting with Jhpiego, which had been appointed by the state to provide technical assistance to operationalize FPLMIS in Jharkhand. The meeting resulted in TCI being asked to support Jhpiego by mapping Accredited Social Health Activists (ASHAs) and Auxiliary Nurse Midwives (ANM) in the FPLMIS system. Jhpiego would then train both groups of community health workers (CHWs) in FPLMIS after the mapping was completed.

When Saifullha Ansari, the City Community Process Manager in Bokaro, witnessed this tracking and its effect on timely information getting to the warehouse for a smooth supply of family planning commodities, he noted that the Public Health Manager used to keep track of commodities but CHWs were closer to the situation on the ground.

The FPLMIS training was welcomed by the CHWs as well. An ASHA named Pratibha said: Earlier, if there was a stock-out situation, I had to wait for the supply or ask other ASHAs for commodities. But after the training, I know if I raise the indent on time, then I can get the supply of FP commodities on time and meet the needs of beneficiaries during my household visit.”

Effective and efficient supply change management for family planning commodities is essential across health facilities, because of the negative impact stock-outs can have on family planning service delivery and quality.

Urban Family Planning Transformed in Uttar Pradesh, India, with TCI-trained Coaches Post Graduation

Contributors: Praveen Dixit, Nivedita Shahi, Amit Kumar, Hitesh Sahni, Deepti Mathur and Parul Saxena

TCI India guided us in leveraging platforms like the city health coordination committee, DQAC, data validation committee and NUHM review meetings to strengthen urban health. This helped us adopt and lead HIPs & HIIs implementation. With TCI's support, our approach to urban family planning has expanded, driving a significant mindset shift.

Dr. Akhand Pratap Singh

Urban Nodal, National Urban Health Mission, Lucknow

In a ground breaking partnership that began in 2018, The Challenge Initiative (TCI) joined with the health department in the Indian state of Uttar Pradesh to transform urban family planning in Ayodhya (Faizabad) and Lucknow.

Ayodhya graduated from TCI support in February 2021, followed by Lucknow’s graduation in July 2022. Before TCI’s intervention, family planning services were scarce, particularly for those living in poverty around urban primary health centers (UPHCs). Fixed-day static services (FDS), now a cornerstone of the program, were a novel concept, and data validation committee meetings were nonexistent, leaving room for improvement in data quality.

In Lucknow, regular meetings among master coaches became the norm, fostering collaboration and enabling the exchange of insights gleaned from field visits and performance tracking. Dr. Singh, an Urban Nodal overseeing the National Urban Health Mission (NUHM) programs in Lucknow who was identified as a master coach to support HIPs & HIIs implementation, reminisced about the journey, emphasizing the enduring impact of TCI’s initiatives.

“Our team … was proudly given the responsibility of being the master coaches of the city. We met quarterly to discuss field visit findings, monitor facility performance and commodity availability, address family planning issues, and identify coaching needs. Currently, we are focused on coaching private sector providers to ensure family planning services are offered to eligible clients in private hospitals. We’ve selected potential private facilities, sensitized their service providers on the communities’ need for family planning, and coached private providers on how to upload family planning data to the HMIS portal.

Moreover, we’ve coached the District Hospitals’ Chief Medical Superintendent on how to assure the availability and accessibility of postpartum and post-abortion services at their facilities. Even though the TCI program graduated from the city last year, we continued to provide supportive supervision to facilities, reviewing urban family planning data in NUHM review meetings, ensuring weekly fixed-day static (FDS) services in all facilities, and sharing FDS reports on the NUHM WhatsApp group.”

Dr. Tripathi, the NUHM’s Urban Nodal in Ayodhya, echoed Dr. Singh’s sentiments, particularly highlighting TCI’s unwavering support during the COVID-19 pandemic. Despite the challenges posed by the outbreak, TCI’s advocacy ensured the uninterrupted delivery of family planning commodities to the community by ASHAs, as well as reinstating vital services at UPHCs.

“ We have learned many effective strategies from TCI India that we are continuing after graduation, such as making sure there is enough funding for urban family planning in the PIP (Program Implementation Plan), regularly reviewing how the budget for urban health is being used, reviewing the urban family planning program in various meeting platforms, expanding the pool of providers by engaging the private sector, periodically building the capacity of service providers, and ensuring convergence of service across departments. The convergence platform has not only aided in improving the quality of family planning services but has helped improve other aspects of health, such as locating spaces for health and wellness centers, executing awareness campaigns of dengue and malaria, and improving other health programs as well.”

The successes in Ayodhya and Lucknow are evident in their HMIS data, which shows a continued increase in annual client volume post-graduation. In Ayodhya, the percentage rose from 250% to 506% two years after graduation (Feb 2021), while in Lucknow, it increased from 166% to 199% within seven months of graduation (July 2022).

Dedicated Medical Officer in Gaya, India, Transforms Community’s Healthcare Access with TCI Support

Contributors: Archana Kumari, Ajay Kumar, Deepika Anshu Bara, Vivek Maviya and Manish Saxena

Seeing low community awareness, I pushed for monthly outreach camps instead of quarterly ones. With TCI’s support, we strengthened partnerships, set up a family planning corner and improved service delivery. These efforts enhanced healthcare access, increased patient trust and boosted the uptake of health services.

Dr. P.K. Verma

Medical Officer-In-Charge, Katari Hill Urban Primary Health Center, Gaya, Bihar

Dr. P.K. Verma – Medical Officer-In-Charge (MOIC) of the Katari Hill Urban Primary Health Center (UPHC) in Gaya, India – noticed a gap in community awareness regarding government-provided health services. Concerned about the well-being of vulnerable populations, he embarked on a mission to improve healthcare access and trust in the system.

During a recent City Coordination Workshop (CCW) in Gaya, Dr. Verma asked: “Why are outreach camps limited to one per quarter? Why shouldn’t they happen every month?”

Dr. Verma is the rare medical professional who is driven by a deep desire to improve healthcare access for underserved communities. And The Challenge Initiative’s (TCI’s) partnership with the Bihar government provided the perfect platform for Dr. Verma to implement change.

TCI’s coaching and mentoring empowered Dr. Verma with the high-impact Convergence intervention that effectively integrates family planning and maternal neonatal health services. Additionally, managerial coaching helped him devise micro plans for outreach camps and establish family planning corners at the UPHC. The coaching also touched upon TCI’s intervention for establishing or nurturing women’s health groups, referred to as Mahila Arogya Samiti (MAS), and how to leverage their support in mobilizing clients to the facilities.

The impact of Dr. Verma’s efforts extended far beyond the outreach camps. Recognizing the positive changes taking place, the municipality allocated additional resources to support his UPHC’s initiatives, leading to facility upgrades and improved coordination with ICDS for better community services. Implementing an efficient appointment system and establishing a family planning corner, under TCI’s guidance, further bolstered patient trust and increased patient volume.

Dr. Verma’s enduring commitment to community service has garnered accolades, with the Katari Hill UPHC receiving the prestigious Kayakalp Award for five consecutive years. The Kayakalp Award underscores the importance of cleanliness, hygiene, infection control and patient safety in healthcare facilities, ultimately benefiting patients and the healthcare system at large.

Whole-Site Orientation Strengthens Post-Abortion Family Planning Services at Hospital in Bareilly, India

Contributors: Deepak Tiwari, Samarendra Behera, Deepika Anshu Bara, Dr. Sangeeta Goel, and Deepti Mathur

We ensure post-abortion family planning clients receive respectful care and necessary assistance. Our focus is on quality counseling by maintaining confidentiality, explaining contraception’s role in preventing unwanted pregnancies, ensuring informed choice and addressing client queries to dispel myths and misconceptions.

Dr. Pushpa Lata Shammi

Chief Medical Superintendent, District Women’s Hospital, Bareilly

Master coaches trained by The Challenge Initiative (TCI) in Bareilly – a city in Uttar Pradesh, India – consistently use TCI’s data for decision-making intervention to review the progress of family planning programs.

During a recent review meeting led by master coaches, it was noted that despite the district women’s hospital (DWH) handling a monthly average volume of 300 deliveries and 40 abortions, the utilization of postpartum family planning (PPFP) and post-abortion family planning (PAFP) services remained insufficient. Moreover, deficiencies in record-keeping practices were identified, leading to inaccurate reporting on PPFP and PAFP uptake.

Recognizing these shortcomings as missed opportunities, especially given the high demand for family planning during the postpartum and post-abortion periods, the master coaches collaborated with TCI to take action. They decided to present their findings to the Chief Medical Officer (CMO) and request permission to conduct a comprehensive orientation for all DWH staff, aimed at fostering a supportive environment for family planning services amidst the high workload.

Dr. Pushpa Lata Shammi, the Chief Medical Superintendent of DWH, shared what happened as a result of the WSO:

“With case studies and other practical examples, we oriented the entire clinical and non-clinical staff of DWH on postpartum and post-abortion family planning services. Soon, we observed a marked improvement in the staff’s working practices, as proper record-keeping and regular HMIS reporting started. The staff nurses sounded more confident in providing family planning counseling and services to post-abortion clients, which wasn’t happening before.”

In fact, after the WSO, Dr. Pushpa started paying extra close attention to the data related to the number of deliveries, abortions, and patients accepting family planning. She now makes sure family planning data reports are made on time and are accurately reported in the HMIS. Because of these efforts, the percentage of women accepting a family planning method at the Bareilly DWH after an abortion has grown from 33% in 2020-21 to 83% in 2022-23.

Integrating Family Planning Services into Health, Sanitation and Nutrition Days in Bulandshahr, India

Contributors: Vishal Saxena, Indra Bhushan Srivastava, Parul Saxena and Deepika Bara

Most women in the area flocked to the UHSNDs for child vaccinations. The regular coaching from The Challenge Initiative (TCI) to broaden family planning services offered at various service delivery points ensures the ready availability of those services alongside vaccinations. There's an untapped potential for the family planning basket of choice, and it could be used not just as a resource but as a means to raise awareness about FP services and offer quality counseling to clients.

Dr. Shashikant Rai, Urban Nodal Officer

Bulandshahr, Uttar Pradesh

During a recent National Urban Health Mission (NUHM) monthly review meeting, Dr. Shahsikant Rai, the Urban Nodal Officer in Bulandshahr – a city in Uttar Pradesh, India – proposed that some undesignated funds be used to procure modern contraceptive methods known as the family planning “basket of choice.” These methods would then be offered to women during Integrated Urban Health, Sanitation and Nutrition Days (UHSNDs).

Dr. Rai’s initiative resulted in a decision to allocate funds from the Mahila Arogya Samiti (MAS) budget to procure the basket of choice. This basket was made available at every UHSND session through Urban Primary Health Centers (UPHCs), with a dedicated medical officer overseeing its distribution. Progress was regularly assessed during monthly meetings, leading to the widespread availability of the basket of choice at every MAS in Bulandshahar, where family planning counseling was actively offered. Clients in need were also referred to family planning services.

Mamta Devi, a MAS member, played a significant role. During MAS meetings, Devi and her fellow members identified couples not using any family planning method. Collaborating with community health workers (CHWs) – such as auxiliary nurse midwives (ANMs) and accredited social health activists (ASHAs), supported by TCI coaching – they provided information and advice on various family planning methods, giving couples a choice to pick the one that suited them best. Together with ASHAs, they prepared baskets of choice and distributed them at every UHSND session.

Thus, a small initiative from an Urban Nodal Officer, along with the efforts of the MAS and CHWs, left a lasting impact on Bulandshahr. The unrestricted funds were not merely spent, they were actively invested in the future of women and families. This story of transformation – from a simple directive to an empowering movement – showcases the incredible potential of community-led healthcare initiatives.

Urban Primary Health Centre Map Guides Appropriate Resource Allocation in Bhagalpur in Bihar State, India

Contributors: Naveen Kumar Rai, Deepika Anshu Bara, Vivek Malviya, Manish Saxena and Deepti Mathur

The idea behind developing this catchment area map is to assist UPHC staff, especially the medical officer-in-charge (MOIC), Auxiliary Nurses and Midwives (ANMs) and ASHAs, to identify their catchment area and the location of all nearby facilities.

Mani Bhushan, District Program Manager

Bhagalpur, Bihar

Some health facilities in Bhagalpur, Bihar, were facing the challenge of disproportionate areas covered by Accredited Social Health Activists.

Bihar state government and TCI India had first engaged in July 2022. TCI India’s proposed solution was to develop a "UPHC Catchment Map," to clearly demarcate the facility catchment area, district hospitals, medical colleges, and a ward-by-ward view of the population, wards, and members of women's health group, referred as Mahila Arogya Samiti (MAS).

Mani Bhushan, the District Program Manager (DPM), welcomed the idea and sought TCI's technical coaching in developing the same for one of the facilities. Thus, facility maps were prepared and displayed in the outpatient department (OPD) area. A copy of the same map was shared with Bhushan, who was delighted to clearly see the boundaries of each facility and use it for plotting population-based resources and seeking more resources wherever it was required. At a scheduled National Urban Health Mission (NUHM) review meeting, he presented the map to Bhagalpur's Civil Surgeon (CS).

Bhushan also mentioned to the CS that these maps were developed with TCI's technical coaching along and inputs from the District Immunization Officer, District Monitoring & Evaluation Officer, Urban Consultant and MOICs. The CS appreciated the idea of the "UPHC Map" for better planning and decision-making. He asked the DPM to work with TCI and develop similar maps for all of Bhagalpur's facilities. The facilities then reached out to TCI to request coaching so they could also develop these maps.

The MOIC started noticing benefits from the mapping, as he observed that ASHAs were utilizing this map for micro-planning activities such as fixed-day static services, outreach camps, community mobilization and immunization. TCI's city implementation leads also shared these learnings and success stories with the CS and district officials for their cities.

As a result, all 50 UPHCs in Bihar's seven TCI-supported intervention cities developed their UPHC maps and proudly displayed them on the walls of their OPD.

Strengthening Postpartum Family Planning Services with IUCD Provision in Urban Facilities of Dhanbad, Jharkhand

Contributors: Prem Kumar, Sunil Kumar, Nilesh Kumar, Dr. Sangeeta Goel and Deepika Anshu Bara

I appreciated the coaching that the UPHC and UCHC staff and the entire district health team were receiving from TCI as it was making a lot of difference. Infrastructure, equipment, trained providers, uninterrupted FP supplies, and commodities must be ensured and then only the community will accept and acknowledge the services.

Dr. Sanjeev Kumar Prasad, District Reproductive and Child Health Officer.

Dhanbad, Jharkhand

The district urban health manager (DUHM) engaged with The Challenge Initiative (TCI) for a coaching session and noted the lack of postpartum intrauterine contraceptive device (PPIUCD) service at Dhanbad.

Sindri urban primary health center (UPHC) and the Gaushala Sindri urban community health center (UCHC) offered delivery services and temporary family planning methods but not PPIUCDs despite being delivery points.

In a subsequent coaching session, the DUHM with support from the TCI team conducted a deep dive to identify the potential reasons and next steps for getting PPIUCD services into both facilities.

With support from TCI, providers were already receiving training, and the medical officer in charge was considering ways to improve the existing UPHC infrastructure. Because the time was ripe for the facilities to also start offering postpartum family planning services, a plan was presented to the Civil Surgeon (CS) and Dr. Sanjeev Kumar Prasad, DRCHO, in a family planning review meeting in November 2022.

The CS and Prasad both had questions about the readiness of these facilities and the staff, but after a few additional meetings, the DRCHO approved the plan. He then directed the medical officer-in-charge (MOIC) to initiate PPIUCD services immediately and report back to the CS office.

Prasad also wanted to ensure PPIUCD clients received follow-up care and instructed the MOIC and DUHM to seek the support of the district quality assurance team to improve the quality of family planning services.

After PPIUCD services began at the Sindri UPHC and Gausala Sindri UCHC in November and December 2022, HMIS data has since recorded 20 new PPIUCD clients.

Transforming Lives: Pithampur’s Leap Towards Sanitation Worker Security

Contributors: Dinesh Kumar Pandey, Pankaj Rao Jadhav, Deepti Mathur and Parul Saxena

After my husband, Vishnu Jatav, tragically passed away in a road accident, our family faced an uncertain future. Thankfully, he was covered under the social security scheme. With guidance from PMC and PSI India, I claimed benefits, which have steadied my family and ensured my children's education continues uninterrupted.

Sangeeta Bai Jatav

wife of a sanitation worker under PMC, Pithampur, Madhya Pradesh

In the industrial heartland of Pithampur, Madhya Pradesh, out of a total of 26,811 households, 19.3% (5,191) are connected to the sewer network, while 80% (21,620) rely on onsite sanitation systems, necessitating regular pit cleaning services. To address this, the Pithampur Municipal Council (PMC) has established a faecal sludge treatment plant with a capacity of three kilolitres per day and acquired three desludging vehicles. A workforce of 723 sanitation workers, including 336 PMC workers and the remainder outsourced, manage this work, which involves working in confined spaces, handling hazardous materials. This puts them at a greater risk of various diseases and even fatalities, including death. The Government of India has launched social security schemes for the well-being of sanitation workers.

The Chief Municipal Officer (CMO) of PMC was briefed by PSI India about the findings of the assessment. Prioritizing the safety and security of sanitation workers, it was decided to orient and enroll all sanitation workers in suitable and affordable schemes like the Pradhan Mantri Suraksha Bima Yojana (PMSBY) and Pradhan Mantri Jeevan Jyoti Bima Yojana (PMJJBY).

PSI India supported PMC in organizing orientation sessions for sanitation workers. These sessions, conducted in small groups of 10-12 individuals at convenient times and locations, covered detailed explanations of PMSBY and PMJJBY. Sanitation inspectors and supervisors facilitated the collection of necessary documents from the 336 workers, including Aadhaar card, bank account details, nominee information, and contact details.

Upon submitting the documents to the bank, it was noticed that sanitation workers lacked the minimum balance, halting auto-debits for social security schemes. A consent letter from all 336 workers and a CMO letter authorized the bank to withhold ?456 for enrollment. A detailed list of workers' information, including insurer names, account numbers, customer IDs, and more, was compiled for enrollment.

As linking workers to the scheme wasn't a bank priority, coordination with the zonal office ensured timely processing. Resultantly, certificates were obtained, each bearing the branch manager's seal, linking 336 workers to the scheme. PMC appointed a focal person to streamline the claim process for injury, disability, or death under the scheme.

Rajendra Mishra, CMO, PMC expressed- "In a transformative collaboration with PSI India, PMC has taken significant strides in protecting the rights and lives of sanitation workers. Since April 2020, we have focused on not just strengthening faecal sludge management systems but, more importantly, on the welfare of the workers through enrolment in government-subsidized social security schemes. This effort underscores the value we place on the safety and security of our sanitation workforce and their families. We have developed a learning document with the support of PSI India on enrolling sanitation workers in social security schemes. It serves as a roadmap that other Urban Local Bodies can follow to uplift their sanitation workers."

In Pithampur, the bereaved families of sanitation workers found a glimmer of hope and support through the social security schemes following the tragic loss of their loved ones. These vital benefits provided them not just with financial assistance but also with a sense of dignity in their darkest hours.

TCI Supports Jharkhand City of Bokaro with Strategies to Increase Male Engagement in Family Planning

Contributors: Manjurur Rahman Khan, Deepika Anshu Bara, Sunil Kumar, Nilesh Kumar and Deepti Mathur

With TCI’s support, ASHAs were coached on male engagement strategies, and the facility was equipped for NSV services. Recognizing gaps, I leveraged budget provisions to set up an operating room, eliminating referrals and missed opportunities. This led to a significant rise in NSV adoption.

Dr. Anil Kumar

Medical Officer-In-Charge, Chhas Community Health Center, Bokaro, Jharkhand

In the steel city of Bokaro in Jharkhand, India, efforts to involve men in family planning primarily focus on a procedure called no-scalpel vasectomy (NSV). In fact, the entire country holds an “NSV Fortnight” every year from November 21 to December 4 to promote male engagement in family planning. However, in Bokaro, data from the Health Management Information System (HMIS) revealed that only three NSVs were performed there between April 2021 and December 2021.

Fortunately, the situation improved after the city received support from The Challenge Initiative (TCI), which provided guidance and training on male engagement strategies to health workers in Bokaro.

These improved results were due to a number of activities in the area surrounding the secondary hospital and community health center (CHC) in Bokaro, known as Chhas. As part of a demand-generation effort, TCI supported Accredited Social Health Activists (ASHAs), who observed male gatherings called ‘Chauraha,’ where men are encouraged to actively participate in family planning as individuals and partners. While more than 20 ASHAs showed interest after their observations, six or seven of them now include male engagement in their regular work.

The ASHA’s efforts led to increased awareness and demand for NSV in the community and the number of people coming to the clinic specifically seeking a NSV began to rise. However, the CHC did not have the necessary equipment or operating rooms for NSV procedures, so potential clients were referred to a tertiary hospital. But if the tertiary facility wasn’t performing NSVs on that day, clients would return to the CHC, resulting in missed opportunities.

Dr. Anil Kumar, the medical officer-in-charge in Chhas, is a trained NSV surgeon. He recognized this growing interest in NSV among men, but was frustrated with the referral process. TCI worked with Dr. Kumar to review the records of NSV clients at the CHC for the past two months and this data sparked his interest in finding solutions to prevent any missed opportunities.

After TCI showed Dr. Kumar the budget provisions under the program implementation plan (PIP) for his CHC, he realized that he could procure the necessary equipment and convert a storeroom into an operating room within his budget limits. Within a few days, he began performing NSV procedures at the Chhas CHC.

And the 2022 NSV Fortnight also provided an opportunity to promote NSVs as ASHAs in Chhas actively spread the word about the event to generate increased demand. During the 2022 event, all interested individuals seeking NSV services received them at the Chhas CHC. The results were remarkable, as TCI-supported cities performed 200% more NSVs compared to the previous year’s NSV Fortnight.

Shabbir Anwar, the district data manager of Bokaro, acknowledged the support they received from TCI, which he said played a crucial role in improving their performance.

Family Planning Counseling Corners Expand in Jharkhand, India, to Help Clients Choose a Method

Contributors: Sunil Kumar, DeepikaAnshu Bara, Nilesh Kumar and Samarendra Behera

Following the establishment of the Family Planning Counseling Corner at our UPHC, women have become more open and proactive in discussing family planning issues. They are now comfortable clarifying their doubts, seeking answers to their questions, and receiving confidential counseling.

Dr. Rachit Bhushan

Risaaldar Nagar UPHC, Ranchi, Jharkhand

Jharkhand’s capital city of Ranchi had an almost stagnant family planning program before implementing TCI’s high-impact practices and other interventions (HIPs & HIIs). Almost all urban Accredited Social Health Activists (ASHAs) had not had a specific family planning orientation for many years. Urban primary health centers (UPHCs) also needed capacity strengthening to improve documentation.

In collaboration with TCI, city government officials and UPHC staff were promptly coached on HIPs & HIIs. Through early mentoring support, the medical officer-in-charge (MOIC) conducted a facility needs assessment of UPHCs to find gaps, and then develop an action plan to resolve them and start delivering quality family planning services.

Among the gaps identified during coaching discussions were low awareness of modern family planning methods in the community and poor visibility of family planning at UPHCs. Dr. RachitBhushan, MOIC of the Risaaldar Nagar UPHC, noted: “The majority of my FP clients are women. However, they are hesitant to discuss FP with a male doctor. As a result, when a woman arrives at the clinic seeking FP information, she looks for a staff nurse.”

to establish “FP Counseling Corners” at UPHCs, which

complied with the government’s privacy guidelines.

All seven MOICs showed interest and inquired about the requirements of establishing such a corner. They discussed the idea with their staff as well.

The TCI team supported them in creating a prototype layout of an FP Counseling Corner and listed the required materials. The MOICs determined that all the commodities and IEC materials listed were available. All that was required was a “sacrosanct space,” with a table, chairs, and a display featuring family planning commodities, job aids and IEC material. The MOICs made auxiliary nurse midwives (ANMs) responsible for managing the FP Counseling Corner, where they counsel eligible clients and help them make an informed choice when selecting a family planning method.

FP Counseling Corners are being noticed and appreciated by other government officials. The Public Health Manager of Ranchi, Mr. Shishir Roy, stated: “We are noticing the benefits of this concept because people who were previously hesitant to ask for FP commodities now take condoms or OCPs from the FP corner. As a result, FP data is increasing. We are now planning to focus on community mobilization and outreach activities, and I am confident that with TCI India’s assistance, we will achieve even better results in the near future.”

Dr. Rachit is equally happy as he reported that in his UPHC, women are no longer hesitant as they visit the FP Counseling Corner. Dr. Rachit is equally happy as he reported that in his UPHC, women are no longer hesitant as they visit the FP Counseling Corner. He now wants to have a female gynecologist scheduled on particular days at the UPHC to support the provision of both maternal and child health and family planning services. He now wants to have a female gynecologist scheduled on particular days at the UPHC to support the provision of both maternal and child health and family planning services.

The successful demonstration of this approach drew the attention and interest of the government. TCI shared this in review meetings and advocated scaling it up in other TCI-supported cities. As a result, the FP Counseling Corner concept has now been adopted by all the remaining four intervention cities in Jharkhand, including Bokaro, Dhanbad, Deoghar and East Singhbhum.

Amroha’s master coaches are sustaining the impact made during TCI’s direct engagement after graduation

Contributors: AnupamAnand, Samarendra Behera and Parul Saxena

“TCI gave us a mantra to leverage the support of other departments, which has shown positive results after graduation especially.”

Ahsan Ali

Urban Health Coordinator,Amroha

Uttar Pradesh

The goal of The Challenge Initiative (TCI) is to support the greater self-reliance of local governments to scale up family planning and adolescent and youth sexual and reproductive health (AYSRH) high-impact interventions (HIIs), leading to sustained improvements in urban health systems and increased use of modern contraception, especially among the urban poor. From the onset of engagement with TCI, the local government is set on a path towards self-reliance to transform and sustain an impactful urban family planning program. In February 2021, five cities in Uttar Pradesh, India, successfully transitioned to the graduation phase of TCI, no longer requiring direct coaching and technical support from TCI.

“Since the inception of TCI, we have considered the initiative a part of NUHM. In February 2021, Amroha moved to the graduation stage. And since then, we have not faced any major challenge. Since graduation, I have mainly utilized approaches such as using data effectively, fixed-day static (FDS) service, strengthening urban ASHAs and convergence for implementation and to coach staff of the health department. The best part is without any follow-up every Thursday all urban primary health centers (UPHCs) are organizing weekly FDS/Antral diwas because facility staff, ANMs (auxiliary nurse midwives), and ASHAs (accredited social health activists) are well-coached on their responsibilities, and FDS reports are timely submitted to us.

In large convergence platforms, like District Health Society, NUHM, and FP Review meetings, I present urban family planning data and ensure action points are developed and adhered to. Based on family planning HMIS data, I prioritize low-performing UPHCs and, along with Nodal Sir [another master coach], plan a regular visit to the facilities. Through these joint visits, I coach UPHC staff and support them in mitigating challenges. Recently, I resolved the supplies issue by taking the support of the FPLMIS Manager, also coached by me. He reoriented the UPHC staff on the online indenting process, and this step has improved the family planning results of low-performing UPHCs.

The quarterly city coordination committee meetings are conducted timely, and I ensure that representatives of other departments accomplish tasks assigned to them.

The only challenge we have faced is to coach newly appointed urban ASHAs regularly, as this is not a stable position. For this, we took advantage of the ASHA and ANM monthly meeting as a capacity-building platform to mentor new ASHAs on family planning counseling skills through ANMs. We ensure that in each ASHA and ANM meeting, staff from NUHM department participates and coaches the community health workers on any relevant health topics and sets their monthly priorities.

Moving forward, we are strengthening the use of the 2BY2 prioritization tool to assist ASHAs to prioritize their family planning clients, and help make timely decisions based on the aggregated 2BY2 matrices.”

TCI’s master coaches are ensuring that the impact created during TCI’s direct engagement is sustained. Their continued role in capacity transfer, decision-making and oversight of implementation of the high-impact interventions is making a noticeable increase in Amroha’s annual family planning client volume at the UPHC and city level – which includes UPHC and district level facilities.

The graph shows the 40% and 14% increase in annual client volume at the UPHC and city level, respectively, for two fiscal years (i.e., from April 2019-March 2020 to April 2020-March 2021). Similarly, HMIS data on intrauterine contraceptive devices and Antara (injectable contraceptive) uptake at the UPHC and city level in the last six months after graduation indicates that the city’s performance following the worst period of the COVID-19 pandemic is back on track both at the UPHC and city level.

The UPHC staff’s Whole-Site Orientation aided in the establishment of adolescent-friendly primary health care facilities

Contributors: Umam Farooq Khan, Parul Saxena, Ipsha Singh and Deepti Mathur

In Dec. 2020, TCIHC's virtual coaching not only helped me overcome my biases related to the provision of contraceptives based on age, parity, and marital status but also equipped me to coach my UPHC staff on providing adolescent-friendly health services, including sexual and reproductive services.

Dr. Arshiya Sherwani

UPHC NaglaTikona,

Aligarh, Uttar Pradesh

The Challenge Initiative for Healthy Cities (TCIHC) in Uttar Pradesh, India, aims to increase access to sexual and reproductive health (SRH) information and services for adolescents and youth in urban environments. TCIHC is partnering with the Government of India’s national adolescent health program called Rashtriya Kishor Swasthya Karyakram (RKSK) to offer adolescent-friendly health services (AFHS) at urban primary health centers (UPHC) for the urban poor.

Because UPHCs are nested within complex social and cultural settings, health service providers working at UPHCs maintain their own beliefs and value system. Healthcare systems can also influence provider actions in the form of policies and norms. These influences may induce provider biases, leading to a lower quality of care, especially for unmarried adolescents.

To address this, TCIHC coached RKSK to launch its high-impact whole site orientation (WSO) best practice to orient all staff in an UPHC on the SRH needs of adolescents and youth. The WSO also addresses any biased attitudes and beliefs towards youth SRH issues that staff may hold that could unintentionally cause harm. Working within the health system, TCIHC in collaboration with RKSK coached the Medical Officers In-Charge (MOICs) of the UPHCs to conduct WSO without TCIHC or RKSK support for all facility staff to create a more enabling environment for adolescents that also ensures quality adolescent-friendly health services.

has facilitated WSO with her staff. In the interview below, she shares

with TCIHC her experience and reflections on the changes

she has observed after WSO.

Discovering my own biases

The coaching I received was in fact a behavior change intervention aimed at reducing my own bias. Unsurprisingly, I discovered that social norms were driving my biases. The most pervasive social norm was the significance of sexual abstinence before marriage. And, therefore, my attitude and belief was that contraceptives were meant for married couples only. I recognized that my attitude towards the provision of contraceptives is shaped primarily by client’s age, parity and marital status. I realized youth must pass through many barriers to access SRH. Provider bias is one of the gates. TCIHC provided orientation material based on RKSK guidelines. I received ‘how-to-guidance’ on conducting a values clarification exercise through a whole site orientation for all staff.

After equipping myself, in January 2021, I conducted WSO sessions for my entire UPHC staff at the facility irrespective of cadre and technical skills, which included staff nurse, lab technician, pharmacist, Auxiliary Nurse Midwives (ANM), Accredited Social Health Activists (ASHA), support staff etc. With support from TCIHC, I attended a youth-led City Consultation Workshop (CCW) in Aligarh organized by RKSK. Here I had heard adolescents and youth candidly share their opinions and desires on SRH issues. I was a bit shocked but I immediately realized the necessity of SRH care for unmarried adolescents and youth. TCIHC initiatives – the AYSRH CCW and WSO – both changed my mindset about the importance of providing SRH information and services to adolescents and youth.”

Facilitating a whole-site orientation

“Facilitating the WSO session was a learning experience for me. The design of activities, such as role plays and cases studies, enabled my staff to overcome non-technical biases rooted in attitudes and beliefs, without explicitly saying that they are doing this. An interesting attitude that emerged was that of staff engaging with young clients from parental perspective. The belief that we are in a better, more informed position to make decisions for clients. I encouraged WSO participants to raise concern without hesitation. This created a non-threatening environment for them to ask and clarify their indecisions. I addressed their questions related to menstruation, puberty and physical changes associated with adolescence. While it was difficult, I was determined to discuss contraceptive needs and behaviors of unmarried adolescents and teenagers and invested time in discussing this topic.

The session on values clarification challenged staff to explore the reasons behind their beliefs, and also reflect on the consequences of their actions when clients are denied contraceptive methods. I tried role plays with the help of the game ‘BhrantiaurKranti’ (Myth and Revolution) from RKSK’s Peer Educator Training Manual. ASHAs enacted the role of Bhranti who asked questions and Kranti who responded with correct answers with rationale. This game helped in busting myths about SRH needs of adolescents – married or unmarried. Apart from this, I also coached the facility staff on the competencies required for delivering SRH services in a friendly manner, like being non-judgmental, maintaining confidentiality and privacy, building trust, interpersonal skills, etc. I covered topics of nutrition, non-communicable diseases, substance misuse, violence and mental health. This orientation aided staff to recognize and address their unconscious biases related to SRH needs of adolescents, which were mainly associated with gender, marital status and age. I was motivated to see the City Community Process Manager from the National Health Urban Mission (NUHM) participate in the WSO. Meanwhile, through the session, I endeavored to sensitize the staff towards SRH needs of adolescent and covered standards set by RKSK for AFHC [adolescent-friendly health clinic].”

After coaching

“After the WSO, I witnessed an explicit change in the attitude of UPHC staff. I observed them being mindful of adolescent needs and being empathetic when counseling them during facility Adolescent Health Days (F-AHDs). WSO had truly prepared the staff. After this, with TCIHC’s technical coaching on F-AHD and detailed coaching on how to organize it, we started F-AHDs on the fifth of every month. With management coaching of TCIHC, we arranged reporting formats, sanitary napkins and medicines for adolescents from the Nodal Officer for F-AHDs. We also established a counseling corner for adolescents to maintain confidentiality and privacy. My team of staff nurses and ANMs along with TCIHC-coached ASHAs and Anganwadi worker publicize F-AHDs and encourage adolescents to use the services. These community health workers motivate adolescents from urban health nutrition day and slum areas. Through F-AHD, we promote health-seeking behaviors among adolescent boys and girls and provide services like hemoglobin testing, body mass index screening and provide iron folic acid supplements (WIFS) and albendazole capsules, as required. Additionally, counseling services are offered to each visiting adolescent where they are counseled about nutritious and balanced diet, mental health issues, genital and menstrual hygiene, among other issues.